Vectors of plant pathogenic risks

Author(s): проф.д-р Оля Караджова, ИПАЗР “Н.Пушкаров” в София; Марияна Лагинова, директор в ЦЛКР

Date: 21.06.2016

5260

One of the major challenges for agriculture in the present century is to ensure food for the progressively increasing world population by raising yields through the use of a sustainable, environmentally friendly approach. In 2015 the world population was 7.4 billion, but the World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that by 2050 it will increase to 9 billion (UN, 2007). According to George Agrios (1997), pests of agricultural production (before and after harvest) reduce global yields by approximately 40%.

In recent years, epidemics of new and formerly known plant diseases have emerged. They cause significant damage in the new territories they invade as a result of changes in the virulence and aggressiveness of the pathogen, the range of host plants, the degree of infestation, etc. A large number of these high-risk pathogens (viruses, mycoplasmas, bacteria) are transmitted by insects (aphids, leafhoppers, whiteflies, thrips), mites and nematodes. Therefore, the accurate identification of pathogens and vectors, knowledge of the epidemiology of pathogens, the biology and behavior of vectors, the efficiency of pathogen transmission and the factors determining it are key prerequisites for the successful implementation of measures within plant pathogen control systems.

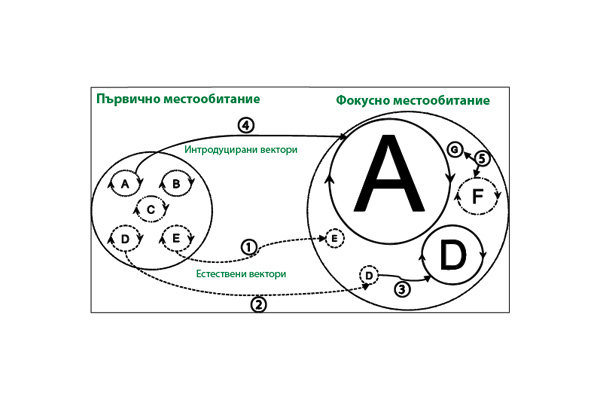

The potential for the emergence of epidemics of diseases in humans, animals and plants through the introduction of vectors into new territories is shown in Fig. 1.

On the left side of the figure, pathogen strains (A, B, C, D, E) are presented, which are maintained in endemic disease cycles in the primary habitats by various types of vectors (dashed lines in the circle). Introduced vectors are represented by solid lines, and local (native) ones – by dashed lines. On the right side, the grey circles represent epidemic disease cycles in potential hosts (humans, animals, plants), with the size of the circle corresponding to the scale of the epidemic. In this scenario, in the endemic cycle several pathogenic strains are maintained in primary hosts for an indefinite period of time by local vectors. Sometimes local vectors infect a terminal host in the epidemic cycle by chance (1) or spread to other hosts (2). In addition, the local vector may acquire the pathogen from a host in the epidemic cycle and, by infecting a new host, cause a large-scale epidemic (see D (3)). When introduced vectors (4) acquire a local pathogen, an epidemic may develop in a new host (see A), which is of enormous scale. It is also possible that introduced vectors may introduce completely new pathogens (5) into the focal (local) habitat, which may cause epidemics in new hosts (F) or infect hosts without major consequences (G). Reverse transmission of pathogens by vectors – from epidemic to endemic cycles – is also possible, creating reservoirs of pathogens for future epidemics.

An example of the emergence of an epidemic of a new disease following the introduction of a new vector is Pierce’s disease of grapevine in California, USA (Almeida et al., 2005). The causal agent of the disease is the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa and, although the pathogen has been present in California for more than 100 years, only three major epidemics have been recorded during this period. The first occurred at the end of the 1800s in Southern California and caused enormous damage to vineyards. The second epidemic of Pierce’s disease occurred between 1930 and 1940 in Central California and was associated with infected leafhoppers that migrated from alfalfa fields located near vineyards. In subsequent years, Pierce’s disease of grapevine was detected at low incidence in the coastal valleys of Napa and Sonoma. The third major epidemic was recorded in 1999, following the introduction in 1989 into Southern California of the invasive vector – the leafhopper Homalodisca vitripennis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). In the new habitat of H. vitripennis the complex of natural enemies is absent and the species multiplies to very high population levels. The presence of a large number of vectors is the main prerequisite for epidemics of Pierce’s disease of grapevine in Southern California and in the southernmost region of the Central Valley. A large number of individuals of H. vitripennis overwinter on citrus (thousands of individuals per plant). Compared to other leafhopper species, H. vitripennis is also characterized by its ability to disperse very rapidly. Two cycles of pathogen spread in vineyards have been identified – the first in spring, when adult individuals migrate from citrus orchards to vineyards, and the second when the new generation appears in summer, acquires the bacterium from infected plants and transmits it to healthy ones. Since citrus is not a host for the bacterial strains that infect grapevine, it is assumed that pathogen spread in the second cycle is the cause of the mass epidemics of Pierce’s disease. Although the environmental factors influencing the occurrence of epidemics of Pierce’s disease in California have not yet been fully clarified, it is considered that the high population density of vectors is an important component of this system. Compared to other leafhoppers, H. vitripennis is a poor vector of X. fastidiosa in grapevine. The occurrence of epidemics in California is mainly due to the invasive vector which, although transmitting the bacterium with low efficiency, compensates for this through its very high numbers in nearby citrus orchards. The ecological and behavioral characteristics of H. vitripennis contribute to the mass spread of the pathogen in vineyards.