The first frost arrives later and later: how shorter winters affect agriculture in our country

Author(s): агроном Роман Рачков, Българска асоциация по биологична растителна защита

Date: 27.11.2025

1107

Frosty days in our country arrive up to two weeks later. This provides a chance for better yields and a second crop. Agronomist Roman Rachkov comments on how this change affects agricultural crops in our country and our agriculture as a whole, what are the positive aspects, are there risks and negative consequences, as well as ways to adapt to these climate changes.

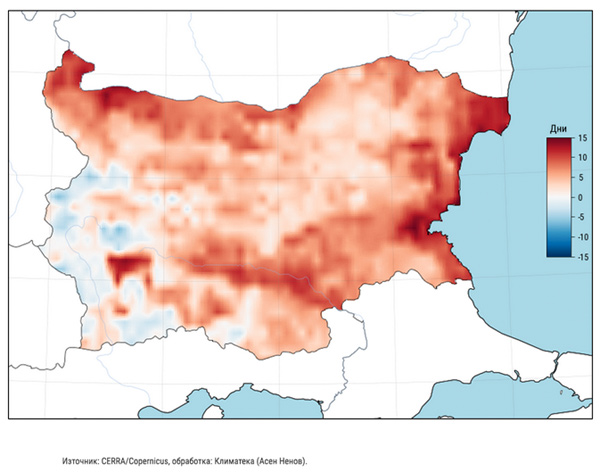

Data from climate analyses clearly show a shift in the first frosts in Bulgaria – in most regions of the country, sub-zero temperatures nowadays occur 5 to 15 days later compared to the end of the 20th century. In practice, this means that winter as a season in our country is shorter, while summer and autumn are extended.

Map: In red are the areas where the first frosts occur later compared to the end of the 20th century, and in blue – the places where the cold spell arrives earlier.

Most noticeably, these changes are observed along the Black Sea coast and in the Thracian Valley, while in mountainous regions, the change is minimal.

Winter recedes: first frosts up to two weeks later

The summer season in the country is extending, autumn is shifting, and the first frosty days are arriving later. In a large part of the country, the first sub-zero temperatures are shifting 5–15 days later compared to the 80s–90s.

The areas with the largest shift forward in time – by 10 to 15 days – are: the Black Sea coast (especially the Northern part) – the most noticeable delay, probably due to warmer sea water retaining heat; the Thracian Valley – with an extended autumn season; Southern Bulgaria (incl. Haskovo and Kardzhali regions)

A moderate shift (+5–10 days) is observed in Northern and Central Bulgaria – the cold spell arrives about a week later, as well as in the Sofia Field and the Fore-Balkan.

Almost no change or earlier cooling is observed in high-mountainous regions (Rila, Pirin, Stara Planina) – minimal shift or stability in the onset of negative temperatures; in some parts of Western Bulgaria – probably due to local microclimatic effects, such as high plains with good conditions for inversions and fogs, and consequently drops in morning temperatures.

It can be summarized that the change in the cooling period is widespread and climatically significant — in a large part of Bulgaria, frosty days arrive at least one to two weeks later. This leads to: shorter winters, a longer frost-free period, and a longer growing season for plants.

Agronomist Roman Rachkov: Late frosts are a chance for better yields in our country

Climate changes are dangerous for agriculture not so much because of the rise in average temperatures, but because of the increasing unpredictability and frequency of extreme phenomena. In this context, the later onset of the first autumn frosts in recent years can be seen as a positive trend for agriculture in our country.

Evolutionarily, crops originating from the temperate zone end their vegetation not due to the onset of cold, but due to the shortening of daylight.

With the observed change, crops typical for Bulgaria, such as peppers and eggplants, which otherwise develop as perennial crops in their centers of origin, will continue to bear fruit, giving farmers a chance for additional yields and income. For field crops, a longer growing season means the possibility of planting and cultivating a second grain crop – traditional for our country. For example, after harvesting wheat in July, sorghum of short-growing season varieties (e.g., 90 days) can be cultivated, meaning sorghum could be harvested in early October.

Late grape varieties will be able to accumulate more sugar in the grapes, which also means higher income.

Less snow, more risks

The problem for plants and agriculture might not be the shorter winter, but the lack of snow.

According to data as of 2023, a clear warming trend has been observed in Bulgaria over the last three decades. The average winter temperature has increased by about 0.6 °C on a seasonal basis, and in the last decade, the rate of warming has accelerated two to three times. This indicates an intensification of climate change and increasingly frequent manifestations of unusually warm weather during the winter months.

A reduction in the number of days with snow cover is also observed, as well as in the so-called ice days, when temperatures remain consistently below zero. Cold periods are becoming shorter and do not reach the minimum values characteristic of the late 20th century.

Insufficient cold days have a tangible impact on agriculture. Many crops, especially winter cereals, depend on a certain number of days with low temperatures, which aid their normal development. When this period is shortened or absent, plants do not go through the necessary dormancy and hardening phase, which makes them more vulnerable to sudden cold spells or spring frosts.

If there is not enough snow and precipitation, there will be less moisture in the soils. Combined with a lack of cold days in winter, this will lead to lower yields in fruit growing.

According to a study with data from 8 meteorological stations in Bulgaria up to 2018, the last spring frost occurs earlier in recent decades. This can create a risk for plants: if vegetation has already started, spring frosts lead to freezing and a total loss of the harvest, something we observed this year in some regions of the country.

Nevertheless, plants possess the ability to adapt to rhythmic changes. Wheat, originating from Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), is proof that crops can adapt to warmer and drier conditions — an important message for the future of agriculture in our country. Adaptation to changes is not the problem; the problem lies with extreme phenomena that lack rhythmicity. Nothing can be applied to them except mandatory crop insurance. In any case, a complex crop rotation with different crops would be more stable and sustainable compared to our current agricultural system.

Winters in Bulgaria are shortening, and the first frosts are occurring later and later – especially along the Black Sea coast and in the southern regions. A trend that also brings benefits: the longer growing season offers a chance for a second yield, but also requires new approaches in soil and water resource management. The adaptability of plants is proven, but the adaptation of agriculture depends on the decisions we make today.

Materials used in the publication are from:

- climatebook.gr

- https://www.climateka.bg/zashto-zimite-ne-sa-tova-koeto-byaha-pressclub/

- CHARACTERISTICS OF FIRST AND LAST FROST OCCURRENCES AND THE LENGTH OF FROST-FREE SEASON IN BULGARIA, 2021

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/заглавна-зимни-мразове.jpg)