Economic importance, biological features and agrotechnics of cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.)

Author(s): Георги Костов, Аграрен университет, Пловдив

Date: 01.08.2025

1519

Summary

The cultivation of agricultural crops is accompanied by a set of technological operations that must have economic justification and benefits. Cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) is known as the oldest fiber crop used by humans. It is widely used not only in the production of fabrics, but also in folk medicine and because of its valuable seeds. The present article examines the economic importance, biological characteristics, uses and agrotechnology of cultivated flax in the hope of familiarizing a wide audience with its valuable qualities and supporting its cultivation and spread in Bulgaria.

Origin, economic importance, distribution

Cultivated flax (also known as “lǎn” and “sejrek” in Bulgarian) has been known to humankind for centuries. Archaeological evidence for flax cultivation dates back to 6000 BC and it is considered one of the oldest and most useful crops. Flax originates from the Mediterranean and Central Asia. The earliest evidence that people used wild flax as a textile comes from present-day Georgia, where spun, dyed and knotted wild flax fibers were discovered by a group of scientists led by Dr. Eliso Kvavadze from the Institute of Paleobiology at the National Museum of Georgia, in the Dzudzuana Cave, and date from the Upper Paleolithic, 30,000 years ago. Until the 18th century it was the most important fiber crop worldwide.

Flax fabrics wear out more slowly and get dirty less, which also makes them easier to wash. Clothes made from linen fabrics are durable, hygienic, comfortable, electro-neutral and hygroscopic, providing a pleasant coolness in summer. With the improvement of spinning machines, flax was gradually displaced by cotton, although it is known that flax fiber is twice as strong as cotton fiber. Some of these properties also determine the wide use of flax fiber for technical products – tarpaulins, sails, filters, ropes, while the residues from flax stems are used for special banknote paper and thermal insulation (Kyrchev, 2019).

Flax has been used as a source of food and a natural laxative since the time of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians. It has also been used as food in Asia and Africa (Berglund, 2002; Jhala & Hall, 2010). In the 8th century Charlemagne considered flax so useful and important for the health of his subjects that he introduced laws and special rules for its consumption (Kyrchev, 2019). The unique and diverse properties of flax are reviving interest in this crop. In 2005, approximately 200 new foods and personal care products containing flax or flax ingredients were introduced to the U.S. market (Jhala & Hall, 2010; Morris, 2007).

Flax seeds occur in brown and yellow (golden) varieties. Flaxseed (Fig. 1) is emerging as an important functional food ingredient due to its rich content of α-linolenic acid (ALA, an omega-3 fatty acid), mucilage (6–12%), fixed oil (30–40%), the cyanogenic glycoside linamarin (C10H17NO6), lignans and fiber. The thousand kernel weight (TKW) ranges between 3 and 16 g.

Figure 1. Flax seeds

Flaxseed oil, fibers and flax lignans have potential health benefits such as reducing cardiovascular diseases, atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer, arthritis, osteoporosis, autoimmune and neurological disorders. Flax protein helps in the prevention and treatment of heart disease and supports the immune system. As a food ingredient, flax or flaxseed oil is included in baked goods, juices, milk and dairy products, muffins, dry pasta, macaroni, meat products, etc.

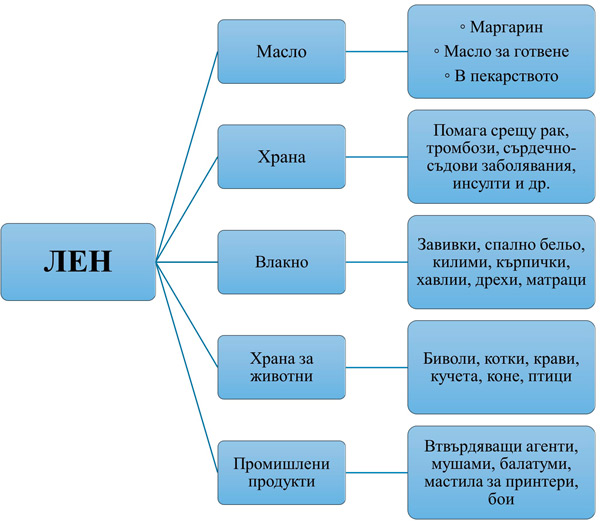

Figure 2. Uses of flax – schematic diagram

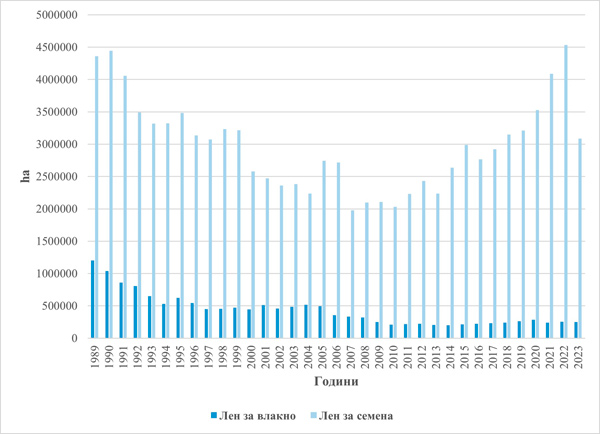

Although flax is classified as a fiber crop, in modern agriculture, due to the valuable qualities of flaxseed oil, its cultivation is practiced to a greater extent as an oilseed crop (Kyrchev, 2019). This can clearly be seen in Fig. 3 below.

Figure 3. Harvested areas of flax for fiber and flax for seed worldwide in the period 1989–2023. Source: FAOSTAT | © FAO Statistics Division

For the period 1989–2023, the harvested areas of fiber flax worldwide decreased by 79.23%, and those of flax for seed – by 29.14%. The largest areas under flax for seed were recorded in 2022 (4,534,773 ha), and the smallest – in 2007 (1,977,659 ha). The largest areas under fiber flax were recorded in 1989 (1,203,442 ha), and the smallest – in 2014 (203,381 ha).

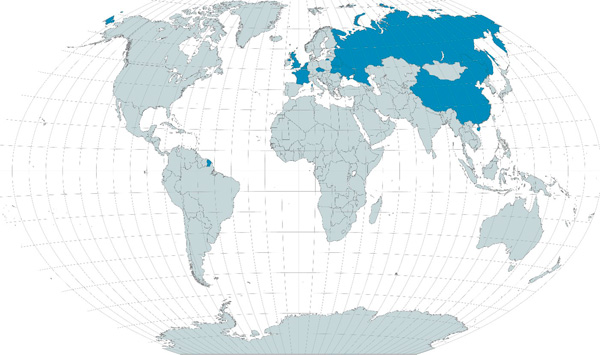

Figure 4. The ten countries with the largest harvested areas of flax for the period 1993–2023. Source: FAOSTAT | © FAO Statistics Division

Biological characteristics. Systematics

Flax is an annual herbaceous plant with a tall stem – from 60–70 to 100–120 cm. Its root system (Fig. 5) is of taproot type, poorly developed, with low absorption capacity. For this reason, it has high requirements for the presence of easily accessible nutrients in the soil.

Figure 5. Root system of flax

The stem is extremely thin (1–2 mm in diameter), cylindrical, with a characteristic absence (or very small number) of branches. The stem of oilseed flax is shorter (up to 50 cm). The leaves are arranged alternately, narrowly lanceolate, smooth, glabrous, with a pointed tip, quite often covered with a waxy coating which gives them a bluish-green tint. When technical maturity is reached, the leaves turn yellow from the base to the top of the stem and gradually fall off. The inflorescence is an umbel-like raceme located at the top of the stem and its branches. The fruit is a spherical 5-chambered dehiscent capsule in which up to 10 seeds are formed (most often 6–8). The flowers are grouped in loose panicles at the top, composed of 5 free sepals (Fig. 6), 5 petals in various colors (for example blue in Linum usitatissimum L., pink in Linum pubescens Banks & Sol., white in Linum catharticum L.), a 5-chambered pistil with styles and wings, and 5 stamens. Flax is self-pollinating, with a low percentage of cross-pollination in this crop.

Figure 6. Fruit capsules and petals viewed from above

Flax belongs to the genus Linum (Flax) of the family Linaceae (Flax family). This botanical family is cosmopolitan and includes about 250 species in 14 genera. The most widespread is common (cultivated) flax Linum usitatissimum L., which includes the following three more important subspecies (Kyrchev, 2019):

- ssp. mediterraneum Vav. et Ell. (Mediterranean) – with plants up to 50 cm high, large capsules and seeds with a thousand kernel weight of 10–13 g;

- ssp. transitorium Ell. (intermediate) – with plants 50–60 cm high and seeds with a thousand kernel weight of 6–9 g;

- ssp. eurasiaticum Vav. et Ell. (European-Asian) – with varying stem height and branching, with small seeds with a thousand kernel weight of 3–8 g.

The latter is the most widespread as a crop. It includes the following varieties (Kyrchev, 2019):

- var. elongata – for fiber;

- var. brevimulticaulia – for oil;

- var. intermedia – intermediate;

- var. prostrata – prostrate (of no substantial importance).

Some flax varieties are Marquis, Impress, Omegalin, Attila.

Phenophases and agrotechnology

During its vegetation, cultivated flax passes through the following phenophases: emergence, “Christmas tree” (18–20 days after emergence), rapid growth, budding, flowering, ripening (green maturity, early yellow, yellow and full maturity). Vegetation period: 85–90 days.

Soil tillage

Because of its small seeds, flax requires a shallow and firm seedbed. The main soil tillage consists of ploughing to a depth of 22–25 cm, carried out immediately after the harvesting of row crop predecessors. With a stubble predecessor, after harvest and removal of the straw, it is more appropriate to first perform stubble ploughing or discing in order to preserve moisture and stimulate weed seeds to germinate (if immediate deep ploughing is impossible for various reasons).

Flax has light and small seeds. This requires that in pre-sowing preparation early in spring the soil be brought to a garden-like condition, with a shallow and firm seedbed. This is achieved with 1–2 passes with a cultivator and harrow simultaneously at a depth of 5–7 cm (Kyrchev, 2019). On grassland fields it is advisable to perform shallow ploughing at 6–7 cm. In mountainous and foothill regions with sloping terrain, the area is ploughed in spring at a depth of 18–20 cm, followed by a shallow surface cultivation.

Flax does NOT tolerate sowing after itself because of the possibility of increasing the incidence of fungal diseases, mainly of the genus Fusarium. Sowing on the same area should be carried out NO earlier than 5–6 years after the last sowing.

Sowing

For sowing flax, very well cleaned seed is used, with a purity not lower than 94% and germination above 85%. Seed treatment must be dry only, because flax seeds become mucilaginous and sticky when moistened.

Sowing is carried out early, when the soil temperature reaches 8℃, i.e. in March–April for the different regions of the country. Sowing is in narrow rows with 7–8 cm row spacing and 2,500 to 3,000 germinable seeds per 1 m2 (≈ 12–14 kg/da).

Fertilization

The application of chemical fertilizers, especially nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilizers, is considered a widely effective agronomic practice for improving crop productivity (Cui et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2020). Flax has a weakly developed root system and has high requirements for the presence of nutrients in the soil that are easily accessible and in a readily assimilable form. According to Ivanova et al. (2019), to form 100 kg of product, plants extract 1.5 kg N, 0.5 kg P2O5 and 1.5 kg K2O. Although in Bulgaria flax is mainly fertilized with mineral fertilizers, very well decomposed farmyard manure can also be used for fertilizing flax.

The rate of nutrient uptake during the different phenophases is undoubtedly different. According to various authors, the most intensive uptake occurs during the phases of rapid growth, budding and flowering. The critical period regarding nitrogen supply is from the “Christmas tree” phase to budding; for phosphorus – from emergence to the “Christmas tree” phase; and for potassium – during the first three weeks of growth, which confirms the need to ensure the vital macro- and microelements.

When nitrogen is deficient or in excess, we observe a decrease in the quality of flax fiber and in yield. Phosphorus is the element that plays the role of an accelerator of ripening and affects fiber quality and yield. It is known that when there are excessive amounts of nitrogen, potassium can neutralize them.

The application of organic fertilizers can coordinate plant growth and soil nutrients, thereby significantly increasing the efficiency of NP fertilizer use, while increasing grain yield and improving seed quality (Cui et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2014). Studies show that the long-term combined application of organic and chemical fertilizers can regulate soil nitrogen runoff, add carbon from soil microbial biomass, and reduce soil nitrogen leaching and groundwater pollution (Cui et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2020a).

The required fertilizers can be applied fractionally, with nitrogen fertilizers applied during pre-sowing soil preparation, and phosphorus and potassium fertilizers – before ploughing.

Crop care during vegetation

These consist mainly of weed, disease and pest control (Kyrchev, 2019)1.

Weed control. Flax is a crop that is strongly suppressed by weeds, and in the case of weed infestation during emergence, stands become thinned. Yield and fiber quality are lower under heavy weed infestation (Tonev et al., 2019). The economically most important weeds in flax among annuals are wild oat (Avena fatua L.), blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.), loose silky-bent (Apera spica-venti (L.) P. Beauv.), common lambsquarters (Chenopodium album L.), etc.; among perennials – field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis L., 1753), thistle species (Cirsium spp.), etc., as well as weeds closely specialized to the crop – flax dodder (Lolium remotum Schrank), rocket (Eruca spp.), flax false flax (Camelina alyssum subsp. integerrima) and others.

At this stage, weed control in flax cannot be highly effective without the use of herbicides. S-metolachlor (Dual Gold 960 EC at a rate of 120 ml/da) can be successfully used after sowing, before the emergence of the crop and weeds, when mixed infestation by annual grasses and broadleaf weeds is expected (excluding wild mustard, Sinapis arvensis L.). During flax vegetation in the “Christmas tree” phase, when flax is infested with annual broadleaf weeds, bentazone (Basagran 480 SL – 200 ml/da) is applied. For the control of annual grass weeds, products with the active ingredients propaquizafop (Agil 100 EC at 75–120 ml/da or Shogun 100 EC also at 75–120 ml/da), quizalofop-P-ethyl (Leopard 5 EC – 100 ml/da), fluazifop-P-butyl (Fusilade Forte 150 EC at 80–200 ml/da) are used.

Disease control. The economically most important diseases of flax are Fusarium wilt, anthracnose, bacterial blight, and brown leaf spots (Kyrchev, 2019). In case of powdery mildew or septoria on flax, tebuconazole (Mystic 25 EW at 100 ml/da) can be applied. Seed treatment, the use of resistant varieties, proper crop rotations and destruction of plant residues are a good way to control diseases in flax.

Pest control. Against flax flea beetle and the circular-mining moth, preparations based on cypermethrin are applied (Poli 500 EC, Cyperkill 500 EC, Cypert 500 EC or Citrine Max, all four at 5 ml/da). Care must be taken with them, given the fact that they are marked SPe8 (dangerous for bees)!

Harvesting

Fiber and intermediate flax (intended for fiber) are harvested at early yellow maturity with flax pullers, and stands intended for seed production – at yellow maturity, again with flax-pulling machines. Besides such machines, harvesting can also be done in a single phase. Oilseed flax is harvested in a single phase at full maturity with a combine harvester.

Flax under changing climate conditions

Climate change is considered the main global challenge affecting human health and food security (IPCC, 2014; Qin et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2020). Several studies indicate that climate change will continue to have negative impacts globally (Antwi-Agyei & Nyantakyi-Frimpong, 2021; Qin et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2020). According to Ali & Erenstein (2017), adaptation practices play a vital role in farmers’ resilience and in mitigating the adverse effects of climate change. However, climate adaptation is complex and depends on various factors, such as farmers’ perceptions, adaptation strategies and the challenges in implementing them (Esfandiari et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2025).

In 2022, François Beauvais et al. published a study on the consequences of climate change on flax fiber in Normandy by 2100. The results indicate that rising temperatures at the end of the century would lead to a shortening of the growth cycle of spring fiber flax. As a result, plant maturity would occur before the end of summer, thus protecting the crop from water shortages. After a dry and warm spring, flax will not accumulate a greater water deficit during its cycle than it does today (Beauvais et al., 2022). Under changing climate conditions, these results could probably be applied to the conditions in Bulgaria as well.

Marketing of production

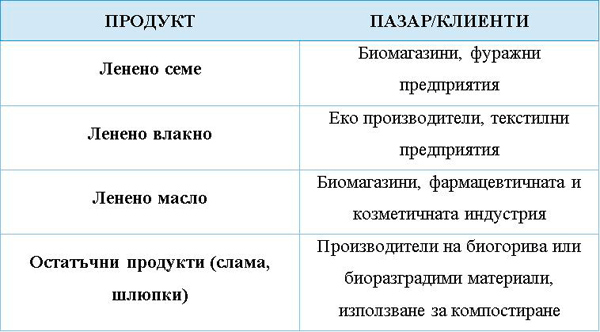

Marketing the production from cultivated flax requires a well-thought-out strategy that must be tailored to the type of product (flax for seed, flax for fiber, etc.) and the scale of production. Different flax products have different markets (Table 1).

Table 1. Target markets for flax products

Direct sales are possible, for example at farmers’ markets. These are extremely popular and particularly suitable for flaxseed oil and seeds. A personal website or online store is also a good option. This marketing channel allows for relatively high profit, is used less frequently and requires an intensive marketing strategy. Other marketing channels may include participation in trade fairs (for example, the Agra fair in Plovdiv or BioFach), contracts with organic shops and pharmacies, and direct contact with processors (mills, organic producers, oil producers or textile enterprises).

For larger orders and exports, it is recommended to join agricultural cooperatives, and for joint processing and marketing – to unite with other flax producers. If production is in larger quantities, it is advisable to look for trade intermediaries or distributors abroad. For large quantities, good alternatives are also participation in platforms such as TradeKey, Agro-Market24, Made-in-Europe, Alibaba, etc., and assistance from the Bulgarian Export Promotion Agency (BAI).

Conclusion

Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.), cultivated as an oilseed or fiber crop, is perhaps one of the most ancient plants altogether (Deyholos, 2006; Kumar et al., 2019). On the Indian subcontinent this crop is grown mainly as an oilseed crop on vast areas. Nevertheless, it is one of the most natural and environmentally friendly textile fibers, especially grown in Europe and China. Flax ranks fourth among the world’s commercial fiber crops (Bolton, 1995; Kumar et al., 2019), which makes it extremely valuable in the textile industry. Moreover, flax has a number of medicinal properties – it acts as an emollient, anti-inflammatory and mild laxative. It is used for colitis, enterocolitis, chronic constipation, urethritis, gastritis and bronchitis, and externally – for arthritis, boils, burns, impetigo and other skin diseases. It is known that the fixed oil also helps with menopause, obesity and arrhythmia.

Flax is a plant of the temperate climate, without sharp temperature fluctuations. It requires a lot of soil and air moisture during budding and flowering. Nevertheless, the agrotechnology of flax is not complicated and allows its cultivation and popularization in Bulgaria. In turn, this would lead to many benefits in everyday life and industry, and why not in agriculture as well.

References

- Kyrchev, H., 2019. Flax. In: IVANOVA, R. (ed.). Crop production, pp. 219–227. ISBN 978-954-517-277-9. Plovdiv: Academic Publishing House of the Agricultural University.

- Scientific Information Center “Bulgarian Encyclopedia”, 2023. Flax. In: KRǎSTEVA, I.; KOZHUHAROVA, E.; ANEVA, I.; ZDRAVEVA, P.; SHKONDROV, A. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants, pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-619-195-356-1. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Knigomania.

- Tonev, T., 2019. Flax and hemp. In: DIMITROVA, M. (ed.). Herbology, pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-954-8319-75-1. Sofia: Videnov i sin.

- Trǎnkov, I. et al., 2005. Cultivation of agricultural crops. Sofia, “Dionis” Publishing House, pp. 165–166.

- Beauvais, F. et al., 2022. Consequences of climate change on flax fiber in Normandy by 2100: prospective bioclimatic simulation based on data from the ALADIN‑Climate and WRF regional models. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 148, 415–426. ISSN 1434-4483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-03938-4

- Cui, Z. et al., 2022. Agronomic cultivation measures on productivity of oilseed flax: A review. Oil Crop Science, 7(1), 53–62. ISSN 2096-2428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocsci.2022.02.006

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT. FAO Statistics Division. Crops and livestock products. Retrieved from: www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- Goyal, A. et al., 2014. Flax and flaxseed oil: an ancient medicine & modern functional food. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 51(9), 1633–1653. ISSN 0975-8402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-013-1247-9

- Jhala, A., & Hall, M., 2010. Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.): Current Uses and Future Applications. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 4(9), 4304–4312. ISSN 1991-8178.

- Karpova, M. et al., 2021. The effectiveness of technological methods for the cultivation of oil flax. BIO Web of Conferences, 37, 1–4. ISSN 2117-4458. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20213700139

- Kumar, A. et al., 2019. Growth, yield and quality improvement of flax (Linum usitattisimum L.) grown under tarai region of Uttarakhand, India through integrated nutrient management practices. Industrial Crops and Products, 140, art. 111710. ISSN 1872-633X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111710

- Qin, Y. et al., 2025. Farmers' perceptions of precision agriculture technologies as a path towards climate change mitigation. Agricultural Sciences/Agrarni Nauki, 17(44), 5–13. ISSN 3033-0149. https://doi.org/10.22620/agrisci.2025.44.001

1 All listed products are current and authorized for use by the Bulgarian Food Safety Agency (BFSA) as of June 2025.

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/заглавна-лен.jpg)

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/фигура-6-плодни-кутийки.jpg)