В Möglichkeiten for use and application of triticale

Author(s): ас. Ивелина Сакаджиева, Институт по земеделие и семезнание "Образцов чифлик" – Русе

Date: 05.05.2025

1593

Abstract

This review article summarizes and analyzes data on the use and application of triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack) – the first plant created by humans. The breeding activities in Bulgaria are examined, with emphasis on the advantages and the potential of triticale for the production of forage, seed and bioethanol, as well as its application in the food industry.

In modern agriculture, the drive for the establishment of environmentally friendly production, the trends towards conservation of renewable resources and a nature-friendly lifestyle lead to a renewed interest in the cultivation of old and rare crops which are not directly related to food production, but are used in the manufacture of ecological, natural and biodegradable products (Berenji, 2008; Serafimov et al., 2020).

Triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack) is an intergeneric hybrid between wheat (Triticum sp.) × rye (Secale cereale L), which combines the high-yield potential of wheat and the disease resistance of rye. The name triticale (Triticale) originates from the Latin names of the two parental components – the first part of Triticum (wheat) and the second part of Secale (rye). The first cross was carried out in 1870 by the English botanist Wilson (Tsvetkov, 1989).

Triticale may be found in octoploid (2n=8x=56), decaploid (2n=10x=70), hexaploid (2n=6x=42) and tetraploid (2n=4x=28) forms, with the first forms being predominantly octoploid, as they combine the genomes of common wheat and rye (Sechniach and Sulima, 1984)

The octoploid forms are characterized by low fertility and are used mainly as a bridge for the transfer of desirable traits from the parental species to the 42-chromosome forms (Tsvetkov, 1989). Decaploid triticale is characterized by reduced vigour, very low grain set per spike and a tendency to revert to a lower chromosome number (Kirchev, 2019). With the creation of the first hexaploid triticale by Derzhavin in 1938, the foundations of future breeding work were laid (Tsvetkov,1989). Subsequently, a number of researchers created many primary hexaploids whose parental forms were the tetraploid wheats Triticum durum and Triticum turgidum and the rye species Secale cereale and Secale montanum (Stoyanov, 2018).

The first tetraploid triticale forms were obtained by crossing 6x triticale with diploid rye (2n=14), but despite their better cytological stability, they were also characterized by insufficient fertility (Tsvetkov, 1989).

A new stage in improving the fertility of the 42-chromosome triticale forms is the development of secondary hexaploid forms based on crosses between 6x and 8x triticale, whose hybrid has become the most successful in practice due to its genetic stability and tolerance to abiotic and biotic factors (Daskalova, 2021).

In Bulgaria, the cultivation of triticale has a history of more than 50 years. Breeding work with the crop started in 1963 and in 1965, at the Higher Institute of Agriculture – Plovdiv, after crossing wheat cv. Bezostaya 1 with the Bulgarian rye cultivar S-2, the first primary octoploid triticale AD-SOS 3 was obtained, and two years later at the Dobrudzha Institute of Wheat and Sunflower near General Toshevo the first hexaploid triticale T-AD was created (Popov and Tsvetkov, 1970).

To date, 19 triticale cultivars have been entered in the Official Variety List of the Republic of Bulgaria: Kolorit, Atila, Akord, Bumerang, Respect, Doni 52 and others. Many of the newly developed cultivars are characterized by high productivity, resistance to biotic and abiotic stress, heavy and well-filled grain, high protein and lysine content, resistance to lodging and shattering, etc. The latest achievements in breeding of the crop are four winter hexaploid triticale cultivars – Galadriel, Rumeliets, Andronik and Helion1, developed at DAI – General Toshevo.

Triticale is used mainly as feed, but it has excellent prospects in the baking and confectionery industry. One of the most valuable qualities of triticale is its high protein content (11–23%), which exceeds that of wheat by an average of 1.5% and that of rye by 3.5%.

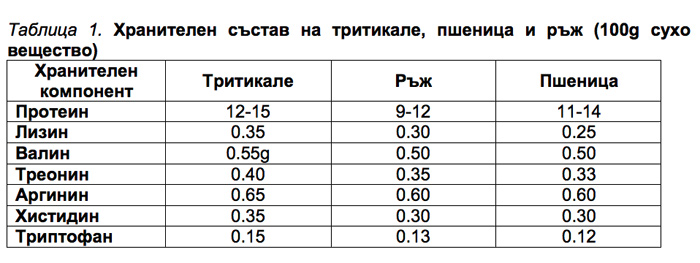

According to Myer and Lozano del Río (2004) and Meale and McAllister (2015), the high content of proteinogenic amino acids in triticale grain is due primarily to the increased proportion of non-essential proteinogenic amino acids relative to essential ones. The content of proline and glutamic acid is most significantly increased. This is important, since proline is associated with drought tolerance in cereals, and glutamic acid is a component of gluten – the cereal protein that largely determines the technological and baking qualities of flour. Extremely important is also the content of lysine, which is the limiting essential amino acid for the biological value of proteins in the grain of cereal crops (Table 1).

In recent years, triticale has increasingly been grown for grazing, silage, hay and feed grain. Both winter and spring triticale types have the potential to meet the needs for green forage for ruminants. The forage quality of triticale is usually slightly lower than that of spring barley and maize, but higher than that of oats (Baron et al., 2015).

The use of triticale grain in bioethanol production has numerous advantages over traditional cereal crops. According to a study conducted by Rosenberger et al. (2002), triticale stands out as a more cost-effective crop compared to wheat and rye. The presence of high levels of endogenous amylases, mainly α-amylase, is crucial for the saccharification of starch into fermentable sugars (Kučerova, 2007; Davis-Knight and Weightman, 2008).

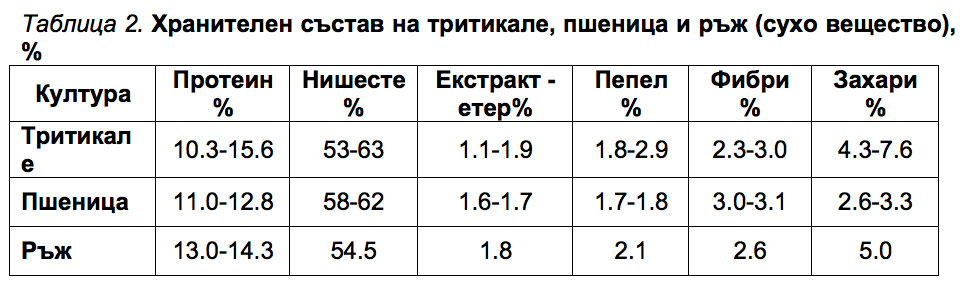

In recent years, numerous studies have been conducted on the baking quality of triticale grain. The data indicate that it is suitable for use in this field, but its utilization has not yet reached optimal levels. According to Peña (2004), the physical characteristics and chemical composition of the grain occupy an intermediate position between wheat and rye (Table 2).

Peña and Amaya (1992) conducted a study in which they found that when wheat and triticale are mixed in a ratio of 75:25 prior to milling, the amount of flour obtained is equal to that from wheat milled alone. In its pure state, triticale flour can be used for the production of rye-type bread instead of mixing wheat and rye grain. Lorenz (1972) notes that white rye-type bread prepared from triticale is fully suitable for consumption. Triticale flour is characterized by a low gluten content and a high amylase content, typical of rye, which is the reason for its low baking quality. If certain technological requirements in its preparation are observed (low mixing speed and reduced fermentation time), bread of acceptable quality can be obtained from some triticale cultivars (Rakowska and Haber 1991).

Triticale is also used in the preparation of dietary desserts. By combining oat and wheat bran (20–40%) with triticale flour, high-fibre bars are produced which are gaining increasing popularity in retail chains (Onwulata et al., 2000).

Conclusions

Triticale has a higher productive potential for grain and biomass yield, high adaptability to different growing conditions, resistance to rusts and powdery mildew, higher protein content in the grain and lysine in the protein, increased tolerance to acidic soils, a more powerful root system allowing it to overcome extreme droughts, and low requirements for soil fertility, which makes it possible to grow the crop on low-productive soils.

Due to its higher protein and lysine content, triticale is a suitable crop to be included in the diet of poultry, pigs and ruminants. Triticale flour is characterized by a low gluten content and a high amylase content. The use of triticale grain in ethanol production has numerous advantages over traditional cereal crops.

References

1. Daskalova N. (2021) Chromosome substitutions in triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack) – a factor for genetic diversity in breeding. Rastenevadni nauki (Crop Science), 58 (2), 13-27.

2. Kirchev Hr. (2019) Triticale – monograph. Uchy media and design, Plovdiv.

3. Marinov-Serafimov P., Golubinova I., Petrova R., Harizanova-Petrova B., Petrovska N., Vulkova V., Blagoeva E., Pavlovski K. (2020) Possibilities for use and application of technical sorghum. Journal of Mountain Agriculture on the Balkans, 23 (6), 149-161.

4. Sechniach L.K., Sulima Yu.G. (1984) Triticale. Moscow, Kolos.

5. Stoyanov Hr. (2018) Response of triticale (×Triticosecale Wittm.) to abiotic stress. PhD Thesis, General Toshevo, Bulgaria.

6. Tsvetkov S. (1989) Triticale. Zemizdat, Sofia

7. Baron V. S., Juskiw P.E., Aljarrah M. (2015) Triticale as a Forage: In François Eudes Triticale, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 10, 189-212.

8. Berenji J. (2008) Scopaeologija – Prošlost, Sadašnjost i Budućnost Metli. In: Zbornik Radova XV Međunarodni Kongres Poljoprivrednih Muzeja, Novi Sad–Kulpin, XV, 40-46.

9. Davis-Knight H.R, Weightman R.M. (2008) The potential of triticale as a low input cereal for bioethanol production. ADAS UK Ltd, Centre for Sustainable Crop Management, Cambridge.

10. Kučerova J. (2007) The effect of year, site and variety on the quality characteristics and bioethanol yield of winter triticale. J Inst Brew, 113, 142–146.

11. Lorenz K. (1972) Food uses of triticale. Food Technol., 26 (II), 66-68.

12. Meale S.J., McAllister T.A. (2015) Grain for Feed and Energy: In François Eudes Triticale, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 9, 167-187.

13. Myer R., Lozano del Río A.J. (2004) Triticale in animal feed. In: Mergoum M, Gómez-Macpherson H (eds) Triticale improvement and production. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome

14. Onwulata C.I., Konstance R.P., Strange E.D., Smith P.W., Holsinger V.H. (2000) High-fiber snacks extruded from triticale and wheat formulations. Cer. Foods World, 45, 470-473.

15. Peña R.J., Amaya A. (1992) Milling and breadmaking properties of wheat-triticale grain blends. J. Sci. Food Agric., 60, 483-487.

16. Popov P., Tsvetkov S. (1970) Hexaploid triticale (2n=42) created by hybridization between T. durum Desf. (2n=28) and S. cereale L. (2n=14). Proceedings of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 23 (12).

17. Rakowska M., Haber, T. (1991) Baking quality of winter triticale. In Proc. 2nd Int. Triticale Symp., Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 428-434.

18. Rosenberger A., Kaul H.P., Senn T., Aufhammer W. (2002) Costs of bioethanol production from winter cereals: the effect of growing conditions and crop production intensity levels. Indust Crops Prod, 15, 91–102.

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/тритикале-заглавна.jpg)