Short overview of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

Author(s): агроном Керанка Жечева, Добруджански земеделски институт – гр. Генерал Тошево, ССА; проф. д-р Иван Киряков, Добруджански земеделски институт – гр. Генерал Тошево, ССА

Date: 11.04.2025

1672

Summary

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is a phytopathogenic fungus attacking more than 400 plant species from 75 plant families. Yield losses caused by the pathogen can reach up to 100%. Under the conditions in Bulgaria, S. sclerotiorum is a key pest in a number of industrial, vegetable and grain legume crops. The present publication provides brief information regarding the distribution, symptomatology, pathogenesis and control measures of the fungus.

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary is a polyphagous pathogen attacking more than 400 plant species, mainly dicotyledonous, from 75 plant families (Boland and Hall 1994). The fungus belongs to the phylum Ascomycota, class Leotiomycetes. The pathogen has been reported in more than 100 countries in Europe, Africa, Asia, North America, Central America and the Caribbean, Australia and New Zealand (Saharan and Mehta, 2008; Cohen, 2023). In Bulgaria, the pathogen is a key pest in a considerable number of industrial, legume and vegetable crops. The damage caused by the fungus is related to the plant species, the resistance of the genotypes, the organs that are attacked and the soil and climatic conditions, and varies widely, reaching up to 100% (Vasconcellos et al., 2017; Rather et al., 2022).

Figure 1. Symptoms caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in common bean

Diseases caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum bear different names depending on the host and the plant organs that are attacked (Sclerotinia wilt, Sclerotinia rot, white rot, white mold, root rot, stem rot) (Steadman, 1983; Bolton et al., 2006; Saharan and Mehta, 2008). The disease symptoms are easily recognizable, due to the formation of white cottony mycelium on the surface of the infected tissues (Hossain et al. 2023). Initially, water-soaked spots of different size and shape are formed on the affected tissues, which subsequently fade, and the infected tissues die.

Figure 1a. Symptoms caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in sunflower (stem form)

Under humid conditions, white cotton-like mycelium accumulates on the affected tissues, which subsequently compacts and forms black structures known as sclerotia (Fig. 1 and 1a). Sclerotia can also be formed inside the infected organs.

Sclerotia are the main source of primary infection. The duration of their survival is influenced by factors such as soil type, moisture and temperature, and their position in the soil. It has been established that under dry conditions sclerotia can remain viable for a period of 7 to 10 years (Adams and Ayers, 1979).

Figure 2. Formation of new sclerotia (arrows) on moistened filter paper.

An experiment conducted by us shows that placing sclerotia on moistened filter paper at 4°C for 40 days leads to their mycelial development and the formation of new sclerotia (Fig. 2) (Zhecheva et al. 2024). These results indicate that the fungus can increase its population in the absence of hosts.

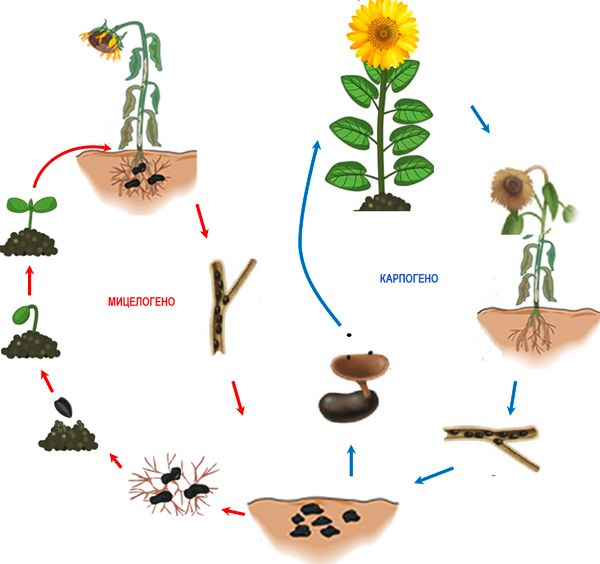

Figure 3. Life cycle of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in sunflower

Infection of hosts follows two main scenarios (Fig. 3). Sclerotia located close to the root system or to plant organs that are in contact with the soil germinate with mycelium (myceliogenic development), which superficially colonizes the tissues while simultaneously producing oxalic acid (Hegedus and Rimmer, 2005; Hossain et al., 2023). The oxalic acid produced suppresses the defense mechanisms of the cells while at the same time increasing the efficiency of cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs) (Hegedus and Rimmer, 2005). The second scenario is related to the fungus entering a sexual cycle (carpogenic development), which leads to the formation of fruiting bodies called apothecia (Fig. 4), from which a significant amount of ascospores is released (Hegedus and Rimmer, 2005). Each apothecium can release up to 10 million ascospores within 7 days, which are carried by air currents and transported over distances of 3–4 km. After landing on the flowers of plants, the ascospores germinate and colonize the senescing organs (petals, sepals, pollen, etc.), after which they attack the adjacent tissues. Infection is favored by wetting of plants for 16–48 h and a temperature of 12 to 24 °C. Most studies show that for sclerotia to enter carpogenic development, a preliminary conditioning of several months is required, during which the sclerotia remain at a temperature of 0 to 5°C and high humidity (Sanogo and Puppala, 2007). The presence of rainfall and an optimal temperature in the range of 20–25°C favors the formation of apothecia and ascospores, but apothecia can also be formed at 5°C (Wu et al., 2008; Phillips, 198; Sanogo and Puppala, 2007; Godoy et al., 2017) or 10–15°C (Gupta and Singh, 2017). Only sclerotia located on the soil surface or at a depth of 3–5 cm form apothecia (Godoy et al. 2017).

Figure 4. Initiation and formed apothecia in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum

The number of apothecia formed on a single sclerotium depends on its size and varies from a few to several dozen. An experiment conducted by us under field conditions shows that sclerotia placed on the soil surface and covered with plant residues from wheat and maize in October initiate apothecial formation at the end of March (unpublished data). No initiation was detected in the variants without plant residues and with plant residues from sunflower. These results indicate that the presence of plant residues on the soil favors the carpogenic development of sclerotia due to maintaining high humidity.

Under the conditions in Bulgaria, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum exhibits predominantly myceliogenic development (Saharan and Mehta, 2008; Genchev and Kiryakov 2002). This fact determines the strategy for control of the pathogen. Crop rotation is a major preventive measure for control of the fungus (Saharan and Mehta, 2008). It is recommended that in fields with proven development of the pathogen, crops that are hosts should not be grown for a period of 4–5 years. Observance of sowing dates and seeding rates can also limit the manifestation and development of the pathogen. Earlier sowings of spring crops create conditions for the death of sprouts and seedlings as a result of myceliogenic development of sclerotia (O’Sullivan et al., 2021). High seeding rates create conditions for prolonged retention of moisture, which favors the formation of apothecia in cases of carpogenic development of sclerotia (McDonald et al. 2013).

The use of resistant varieties or hybrids is considered the most efficient and effective measure for disease control (Schwartz and Singh, 2013). Resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is quantitative in nature, which complicates breeding for resistance (Genchev and Kiryakov, 2002; Schwartzand and Singh, 2013). For example, resistance of sunflower hybrids is associated with the form of disease development – basal, stem and head rot (Castaño et al., 1993; Van Becelaere and Miller, 2004; Davar et al., 2010). Our studies show that hybrids possessing resistance to the stem form are susceptible to the basal form of the disease. In common bean, two mechanisms of resistance are reported (Miklas et al., 2012; Schwartz and Singh, 2013). The first is related to plant growth habit. Varieties with an upright plant habit prevent infection during flowering due to better aeration of the crop and reduced humidity. At the same time, they position the aboveground organs (stems, leaves and pods) at a height that prevents their contact with the soil surface, which prevents infection in cases of mycelial development of sclerotia. The second resistance mechanism is related to anatomical features of the plants that impede the penetration of the pathogen into the tissues. This resistance is known as physiological (Griffiths, 2009; Miklas et al., 1999; Mkwaila et al., 2011; Pascual et al., 2010).

The use of fungicides is one of the most preferred approaches for controlling diseases in cultivated plants. With regard to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, the application of fungicides is justified when there is a risk of carpogenic development of the pathogen, i.e. when plants are attacked during flowering (Peltier et al., 2012; Derbyshire and Denton-Giles, 2016; O’Sullivan et al., 2021). Seed treatment with fungicides prevents infection in the early stages of plant development (Peltier et al., 2012). In cases of direct attack on the aboveground biomass of plants as a result of myceliogenic development of sclerotia, the application of fungicides is not effective.

References

1. Adams, P. B., & Ayers, W. A. (1979). Ecology of Sclerotinia species. Phytopathology, 69(8), 896-899.

2. Boland, G. J., & Hall, R. (1994). Index of plant hosts of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 16(2), 93-108.

3. Bolton, M.D, Thohmma, B.P.H.J. & Nelson, B.D. (2006). Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Molecular Plant Pathology, 7(1), 1–16

4. Castaño, F., Vear, F., & de Labrouhe, D. T. (1993). Resistance of sunflower inbred lines to various forms of attack by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and relations with some morphological characters. Euphytica, 68(1), 85-98.

5. Cohen, S. D. (2023). Estimating the climate niche of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum using maximum entropy modeling. Journal of Fungi, 9(9), 892

6. Davar, R., Darvishzadeh, R., Majd, A., Ghosta, Y., & Sarrafi, A. (2010). QTL mapping of partial resistance to basal stem rot in sunflower using recombinant inbred lines. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 49(3), 330-341.

7. Derbyshire, M. C., & Denton-Giles, M. (2016). The control of sclerotinia stem rot on oilseed rape (Brassica napus): current practices and future opportunities. Plant Pathol. 65, 859–877. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12517

8. Genchev, D., & Kiryakov, I. (2002). Inheritance of resistance to white mold disease (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary) in the breeding line A195 of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.).

9. Godoy, O., Stouffer, D. B., Kraft, N. J. & Levine, J. M. (2017). Intransitivity is infrequent and fails to promote annual plant coexistence without pairwise niche differences. Ecology, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1782

10. Griffiths, P. D. (2009). Release of Cornell 601–606: common bean breeding lines with resistance to white mold. HortScience, 44(2), 463-465.

11. Gupta, M., & Singh, K. (2017). Carpogenic germination and viability studies of sclerotia of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum causing lettuce drop. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 6(8), 2971-2979.

12. Hegedus, D. D., & Rimmer, S. R. (2005). Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: when “to be or not to be” a pathogen?. FEMS microbiology letters, 251(2), 177-184.

13. Hossain, M. M., Sultana, F., Li, W., Tran, L. S. P., & Mostofa, M. G. (2023). Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: Insights into the pathogenomic features of a global pathogen. Cells, 12(7), 1063.

14. McDonald, M. R., Gossen, B. D., Kora, C., Parker, M., & Boland, G. (2013). Using crop canopy modification to manage plant diseases. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 135, 581–593. doi: 10.1007/s10658-012-0133-z

15. Miklas, P. N., Delorme, R., Hannan, R., & Dickson, M. H. (1999). Using a subsample of the core collection to identify new sources of resistance to white mold in common bean. Crop science, 39(2), 569-573.

16. Miklas, P. N., Kelly, J. D., Steadman, J. R., & McCoy, S. (2012). Release of partial white mold resistant pinto USPT-WM-12. Cooperative, 291.

17. Mkwaila, W., & Kelly, J. D. (2011b). Heritability estimates and phenotypic correlations for white mold resistance and agronomic traits in pinto bean. Cooperative, 134.

18. Mkwaila, W., Terpstra, K. A., Ender, M., & Kelly, J. D. (2011a). Identification of QTL for agronomic traits and resistance to white mold in wild and landrace germplasm of common bean. Plant Breeding, 130(6), 665-672.

19. O’Sullivan, C. A., Belt, K., & Thatcher, L. F. (2021). Tackling control of a cosmopolitan phytopathogen: Sclerotinia. Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 707509. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.707509

20. Pascual, A., Campa, A., Pérez-Vega, E., Giraldez, R., Miklas, P. N., & Ferreira, J. J. (2010). Screening common bean for resistance to four Sclerotinia sclerotiorum isolates collected in northern Spain. Plant Disease, 94(7), 885-890.

21. Peltier, A. J., Bradley, C. A., Chilvers, M. I., Malvick, D. K., Mueller, D. S., Wise, K. A., & Esker, P. D. (2012). Biology, yield loss and control of Sclerotinia stem rot of soybean. Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 3(2), B1-B7.

22. Phillips, L. D. (1984). A theory of requisite decision models. Acta psychologica, 56(1-3), 29-48.

23. Rather, R. A., Ahanger, F. A., Ahanger, S. A., Basu, U., Wani, M. A., Rashid, Z., Sofi,P., Singh, V., Javeed, K., Baazeem, A., Alotaibi, S., Wani, O., Khanday, J., Dar, S. & Mushtaq, M. (2022). Morpho-cultural and pathogenic variability of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum causing white mold of common beans in temperate climate. Journal of Fungi, 8(7), 755.

24. Saharan, G. S. & Mehta, N. (2008). Sclerotinia diseases of crop plants: biology, ecology and disease management. Springer Science & Business Media.

25. Sanogo, S., & Puppala, N. (2007). Characterization of a darkly pigmented mycelial isolate of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on Valencia peanut in New Mexico. Plant Disease, 91(9), 1077-1082.

26. Schwartz, H. F. & Singh, Sh. P. (2013). Breeding Common Bean for Resistance to White Mold: A Review. Crop Sci. 53:1832–1844.

27. Steadman, J. R. (1983). White mold, a serious yield-limiting disease of bean. Plant Disease, 67(4), 346-350.

28. Van Becelaere, G., & Miller, J. F. (2004). Combining ability for resistance to Sclerotinia head rot in sunflower. Crop science, 44(5), 1542-1545.

29. Vasconcellos, R. C., Oraguzie, O. B., Soler, A., Arkwazee, H., Myers, J. R., Ferreira, J. J., Song, Q.; McClean, P.; & Miklas, P. N. (2017). Meta-QTL for resistance to white mold in common bean. PLoS One, 12(2), e0171685.

30. Wu, B. M., Subbarao, K. V., & Liu, Y. B. (2008). Comparative survival of sclerotia of Sclerotinia minor and S. sclerotiorum. Phytopathology, 98(6), 659-665.

31. Zhecheva, K., Koleva, M., & Kiryakov, I. (2024). Sclerotinia sclerotiorum genetic diversity in Bulgaria. Bulgarian Journal of Crop Science, 61(5), 97-104.(Bg)

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/заглавна-обзор-керанка.jpg)