Полезни ефекти на микробиалните биостимулатори за растенията

Author(s): проф. Андон Василев, от Аграрния университет в Пловдив; доц.д-р Йорданка Карталска, Аграрен университет, Пловдив; гл. ас. д-р Катя Димитрова, Аграрен университет, Пловдив; Димитър Петков, Агредо ООД

Date: 30.03.2023

1837

The production of microbial biostimulants is most commonly carried out by cultivating microorganisms on various nutrient media. The resulting microbial biomass and metabolic products are formulated as liquid microbial preparations (in a stabilized medium), as dried products (through lyophilization), or are incorporated into a specific carrier (cellulose, dextrose, expanded clay, etc.) or into a suspension.

Microbial biostimulants are applied to seeds, soil (directly or via irrigation and fertigation), or to growing plants. Although the mechanisms of action of microbial biostimulants on plants are not fully elucidated, there is convincing evidence of their positive impact on plant growth. It is now accepted that their effects are due to the stimulation of various processes, the main of which are as follows:

- biological nitrogen fixation

- mobilization of insoluble phosphates;

- production of iron-chelating compounds;

- production of hormones and control of the phytohormonal status.

Beneficial effects of bacteria and rhizobacteria on plants

Biological nitrogen fixation is one of the best-known effects of symbiotic (Rhizobium spp.) and some other microorganisms (Azotobacter spp., Azospirillum spp., Bacillus polymyxa, Gluconoacetobacter diazotrophicus, Burkholderia spp., etc.). Atmospheric nitrogen (N2, 78%) is inaccessible to plants due to the extremely stable triple bond between the two nitrogen atoms. The above-mentioned microorganisms, through the enzyme nitrogenase, have the ability to convert atmospheric nitrogen into the ammonium form (NH4+) available to plants.

The role of symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the nitrogen nutrition of legume crops has long been known. Of greater current interest is the ability of free-living microorganisms to support the nitrogen nutrition of other agricultural crops. The available information in this respect is still limited, but it is assumed that under favorable conditions microbial biostimulants containing free-living nitrogen fixers can enrich the soil with 2–3 kg of nitrogen per decare.

Another mechanism by which rhizosphere bacteria (PGPR) stimulate plant growth is by increasing the availability of phosphorus and iron in the soil. Although the total phosphorus content in the soil is usually high, only 0.1% of it is available to plants due to chemical fixation and low solubility. Microorganisms enable the biological transformation of insoluble inorganic and organic phosphates into forms available to plants. They synthesize and release into the soil environment organic acids and phosphate enzymes (phosphatase and phytase). Organic acids increase the availability of inorganic phosphates, while phosphate enzymes increase the availability of organic phosphates. The main PGPR that have this capacity belong to the genera Burkholderia, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Rhizobium, Agrobacterium, Achromobacter, Streptomyces, Micrococcus, Erwinia, etc. These microorganisms collectively produce low-molecular-weight organic acids that acidify the soil solution and thus increase the solubility of phosphate ions from phosphorus-containing compounds. By dissolving insoluble phosphates, microorganisms can indirectly assimilate a significant portion of P from the soil solution. Upon the death of microbial cells, the phosphorus contained in them is released, which allows its uptake both by plants and by other soil organisms.

Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms exhibit a wide range of metabolic functions in different environments, which leads to significantly higher plant growth, improved soil properties, and increased biological activity. These microorganisms also participate in the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen, accelerate the availability of other micronutrients, produce plant hormones such as auxins, cytokinins and gibberellins; release siderophores, hydrogen cyanide, enzymes and/or fungicidal compounds such as chitinase, cellulase, protease, which provide antagonism against phytopathogenic microorganisms.

A large part of the iron in soils with neutral or alkaline reaction is in a form unavailable to plants, such as the ferric ion Fe(III). Plants have two strategies for iron uptake: strategy 1 by increasing its solubility, followed by reduction to the ferrous ion Fe(II) in the membranes of root cells, and strategy 2 (mainly in cereal species) by exudation of phytosiderophores that form chelate complexes with Fe(III). Rhizospheric microorganisms, similar to cereal crops, can facilitate iron uptake by plants through the synthesis of microbial siderophores (low-molecular-weight chelating compounds). Bacteria mainly produce three groups of siderophores – catecholates, hydroxamates and carboxylates, while soil fungi produce four groups: ferrichromes, coprogens, fusarinines and rhodotorulic acid. Regardless of their nature, they form soluble ferric complexes that participate in iron assimilation and its uptake by plants. It is assumed that the Fe(III)–siderophore complex is formed on the mineral surface, transferred into the soil solution and becomes available for uptake by other organisms. The role of siderophores is not limited only to increasing the bioavailability of Fe, but also includes the ability to form complexes with other essential elements (i.e. Mo, Mn, Co and Ni) in the environment, improving their microbial uptake.

A third mechanism by which microorganisms affect plants is related to the production of plant hormones (or growth regulators), as well as to the control of the hormonal status of plants. It is known that phytohormones such as auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, ethylene, abscisic acid and others regulate a number of physiological and morphological processes in plants.

It has been repeatedly established that ethylene emission decreases in inoculated plants. Ethylene is known as the hormone of ageing. Its precursor in plants is 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC). Under stress conditions, ethylene production increases, limits growth and stimulates ageing in plants. ACC deaminase, produced by microorganisms, has the ability to reduce ethylene levels in inoculated plants and to restore growth processes.

Beneficial effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on plants

Mycorrhiza (ecto- and arbuscular) is a symbiosis between the roots of 80% of terrestrial plants and mycorrhizal fungi. Arbuscular mycorrhiza can play a significant role in the mineral nutrition of plants because it forms a network of hyphae that greatly increases the volume and contact surface of roots in the soil.

Creation of a mycorrhizosphere around the roots by adding mycorrhizal products to the soil

It is known that plant roots occupy no more than 5–10% of the internal volume of the soil; therefore, a large part of the nutrients lies beyond their reach. Fungal hyphae are thinner than the thickness of the “working roots” (0.2–0.3 mm), which is why they have a higher penetration capacity in the soil and accordingly greater access to nutrients and water in the soil. When mycorrhizal products are successfully inoculated, a “mycorrhizosphere” is formed, which facilitates the supply of phosphorus, difficult to access for the roots, and of a number of micronutrients. Glomus spp. is the most widespread genus of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which includes species with a broad and narrower specialization towards specific plant species.

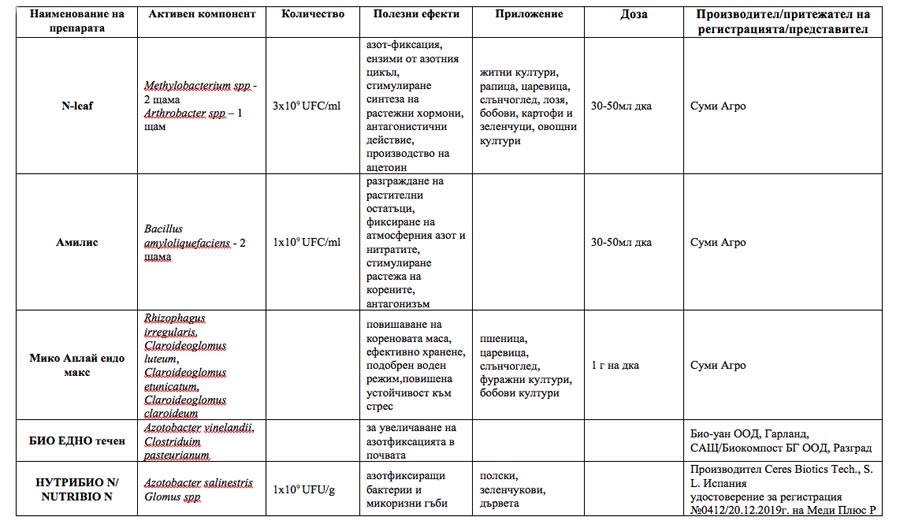

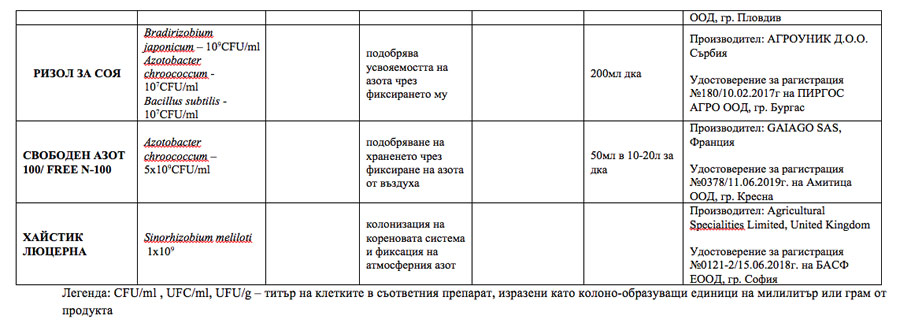

List of approved products for organic fertilization under Eco-scheme 3

The aforementioned beneficial effects of microorganisms provide grounds for businesses to develop and offer appropriate microbial biostimulants on the agri-market. Some of the microbial products authorized in Bulgaria with announced nitrogen-fixing capacity are presented in the table.

Microbial biostimulants included in the List of authorized products in Bulgaria (2022)

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/почва-елементи-1.jpg)