Phenology of plants is an important bioindicator of climate change

Author(s): Растителна защита

Date: 28.03.2023

1628

Phenological observations are of great importance for proper planning and management in agriculture. Worldwide, the onset of phenological phases has accelerated by 3–4 days per decade since 1970. In recent decades this parameter has accelerated by 10–20 days in most parts of the globe.

The significance of the ongoing changes for nature and society can be assessed primarily through the response of ecosystems and the changes in their structural and functional characteristics. Data on what the weather was like at the beginning of seasonal phenomena make it possible to directly assess the relationship with climate change in different regions or the relationship with the intensification of anthropogenic activity, with the changing conditions for the existence of biological communities and organisms. This circumstance explains the noticeable increase in attention to phenology – the science of seasonal changes in nature. Modern phenology is a synthetic science that studies the regular annual seasonal changes in the Earth’s biosphere, the biorhythms of natural complexes and geosystems in different geographical regions, the interrelationships and multifaceted seasonal changes in living and non-living objects in an extensive geographical area. In other words, phenology addresses the problem of studying the seasonal fluctuations of the biosphere.

Seasonal changes on the Earth’s surface manifest themselves in the form of regularly alternating natural phenomena. Each territory has its own seasonal phenomena and calendar time at which they occur. Meteorological conditions are not constant. The concepts of “early” and “late” spring and autumn are well known. Annual fluctuations in the timing of the onset of seasonal natural phenomena are often significant. The system of knowledge about seasonal natural phenomena, the timing of their onset and the causes that determine these timings is called phenology. The term “phenology” was proposed in the mid-19th century by the Belgian botanist C. Morren and, despite the fact that according to many phenologists it is not entirely successful from a philological point of view, it has become established and is used to this day. In a literal translation from Greek: “phainomena” – phenomenon, “logos” – science, I study, that is, “phenology” – science of phenomena.

Importance of phenological observations

Phenological observations are of great importance for proper planning and management in agriculture

Scientific management of agriculture at the current level is impossible without proper planning of the timing of the main agricultural and livestock activities. The start of the sowing period, thinning, weeding, irrigation, fertilisation, haymaking, turning out livestock to pasture; all these activities require mobilisation of labour and technical preparation, and a good manager would not choose to orient himself according to the official calendar. He will orient himself in the natural environment, depending on the phenological characteristics of the year. “Year after year is not the same”, say phenologists. For example, the difference between the earliest and the latest dates for the beginning of cherry blossom in the Japanese city of Kyoto over 10 centuries of observations is 46 days – from 27 March to 12 May. Shorter phenological series generally show less interannual variability. However, observations conducted over several decades usually provide an assessment for most phenomena already within the span of a single calendar month.

Striking, easily noticeable seasonal phenomena – pheno-indicators, whose onset should be perceived as a signal to start work of a certain type, help agricultural workers to understand the seasonal development of nature in a given year. For example, it has been established that near Veliko Tarnovo the best period for planting cucumbers is during lilac flowering. Late planting (even by 5 days) reduces the total yield by 10%.

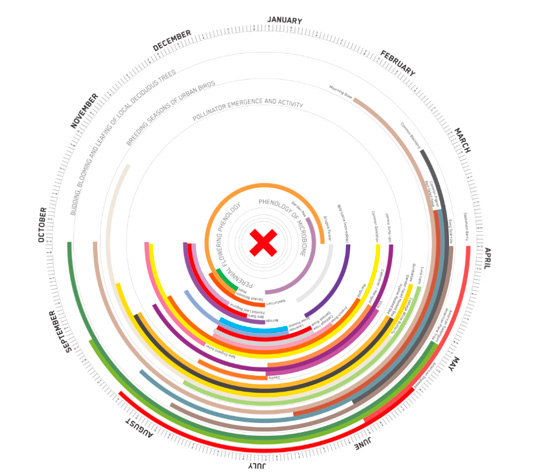

Phenological clock

Knowledge of the specifics of the seasonal development of different varieties of agricultural crops is necessary for their proper placement even on small areas, and all the more so on the territory at a national scale. For example, it is known that in Northern Bulgaria in the lowlands frosts start earlier and end later than on the slopes. Therefore, in the lowlands it is necessary to plant and sow crops and varieties that are early maturing, frost-resistant, with a short vegetation period, whereas on low, slightly inclined ridges and hills, on the contrary, those that are more demanding of warmth should be placed.

The control of harmful insects requires knowledge of the phenology of both the cultivated plants themselves and their pests. For example, according to observations by local gardeners, aphids cause the greatest damage to turnip crops when sowing is carried out at intermediate dates. With early sowing the plants have time to strengthen before the mass multiplication of aphids, and with late sowing they develop after the main feeding period of these insects and do not suffer major damage. It is impossible to get rid of many pests solely by shifting the sowing time – their physical destruction is necessary. Knowing the stages of the seasonal development of pests, phenologists can suggest the period, often very short, when pest control would be most effective.

In pasture-based livestock farming, phenological information on the seasonal development of grass in mountain pastures determines the time for driving livestock to the highlands. Phenological observations help to correctly determine the time for haymaking. Thus, it is known that haymaking at the beginning of flowering of meadow grasses and the onset of seed formation gives higher yields than during full flowering. The quality of hay is higher with early mowing.

In developed countries, and in particular in the USA, phenological information is extremely valuable and farmers annually purchase reference materials with forecasts for the development of their crops.

Flower field with poppies

What is the relationship between phenology and climate change?

Climate change, and in particular the significant change in air temperature, triggers important changes in plant phenological cycles over large areas of the world. These cycles are also called phenophases and are specific biological events that form part of the annual life cycle of plants.

Plant phenology has changed significantly over 54% of the Earth’s land surface since 1981.

according to some studies (Fitchett, Grab, 2015).

While the phenological response to climate change represents a global phenomenon that varies greatly among different regions, it is unanimously recognised that the most evident changes in phenological cycles have occurred in recent decades in the boreal and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere.

However, the extent of phenological changes depends not only on the rate of climate change or other non-climatic factors, but also on the response of plant species to external disturbances. These studies indicate an extension of the growing season (especially in the temperate and high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere), also due to the earlier onset of spring, since temperatures during this season have increased significantly compared to those in past decades. In addition, the delayed autumn season explains to some extent the extension of the growing period in many regions of the planet.

The impact of temperature changes is generally a more determining factor than other environmental variables

Plant phenology is highly sensitive to climate change and is an important bioindicator of climate change. Clear evidence of long-term changes in plant phenology among temperate and boreal regions in the Northern Hemisphere is mainly associated with temperature changes, which represent the main controlling factor of this type of ecosystem dynamics in mid and high latitudes. Although there are other environmental variables that can influence plant phenology, such as photoperiod, precipitation, atmospheric CO2 and nitrogen deposition, the influence of these factors is generally lower than that of temperature.

As a general rule, worldwide the onset of a given phenological phase has accelerated by approximately 3–4 days per decade since 1970. It has been found that this ecological parameter has accelerated by about 10–20 days in most parts of the globe in recent decades. In Europe it has been found that between 1971 and 2000 the acceleration was 2.5 days per decade during spring events and 1.3 days per decade during autumn phases, which underscores the greater significance of spring phenological changes compared to autumn. It is assumed that this indicator has recorded an overall acceleration across the European continent of almost 11 days since 1951, according to phenological records, and has reached approximately 19 days since 1982, according to satellite data.

Changes in phenological events can create numerous risks for natural vegetation and crops, such as increased subsequent damage from harmful insects and frost damage due to earlier manifestations of phenological events. Temporal phenological mismatch can also lead to disruption of key plant–animal interactions, which may alter ecosystem functions.

Moreover, phenological changes can create significant effects in terms of feedback between the terrestrial climate and ecosystem functionality, mainly by altering the photosynthetic activity of plants, carbon uptake and ecosystem productivity. Ultimately, an in-depth understanding of phenological changes can be crucial for a better understanding of the feedback between climate and the carbon cycle and, implicitly, for a better understanding of future climate changes.

What are the applications of phenological observations?

Assessing phenological changes for areas where only climate data are available can provide essential information regarding the response of the ecosystem to climate change. In addition, these types of studies are useful for detecting early signs of ecosystem transitions against the background of climate change in a specific region.

Given this context, the analysis of phenological changes through climatic approaches (based on climatological records), in particular through statistical analysis of the climatic growing season, has the advantage of allowing rapid extraction of phenological information when no phenological records are available for a given territory. However, this approach is considered representative if the phenology of the studied area is controlled mainly by temperature, as is the case in the temperate region where most of the European continent is located – and implicitly Bulgaria.

Therefore, the analysis of the climatic growing season – the period during which plant development can theoretically occur (which is assessed on the basis of certain thermal thresholds within which vegetation can grow) and which does not fully coincide with the period of actual growth — can be an extremely useful tool in analysing phenological dynamics over extensive areas and for long periods of time.

Many trends in the timing of the onset of phenological phenomena reflect climatic variations and serve as important indicators of the changes occurring in nature. This is why in recent years there has been a heightened focus on long-term phenological observation series as a source of information on trends and interannual variability in the state of populations.

In Europe, processes of integrating national phenological networks, standardising observation methods and analysing long-term phenological series are actively underway. This makes it possible to obtain assessments of changes in phenological indicators with wide geographical coverage.

The timing of the onset of phenological phases of development of living nature has shifted in recent decades due to changes in exogenous factors, particularly climate change, and this is manifested more clearly in the continental regions of Europe. Phenological indicators of vegetation development, especially those that have a close relationship with the temperature regime and moisture, can be used as indicators of climate change.

Phenology, as a science that emerged two centuries ago, has accumulated over the years inexhaustible data and evidence of existing patterns of living nature and seasonal changes. The use of phenological observations and research under modern conditions addresses a number of practical problems related to understanding the secrets of nature, teaches us to see living nature in its development and formation, and in practice demonstrates to us the global phenomena associated with climate change.

Materials used in the publication:

- Xiaoyang Zhang; Phenology and Climate Change. 2021

- Fitchett, J.M.; Grab, S.W.; Thompson, D.I. Plant phenology and climate change: Progress in methodological approaches and application. Prog. Phys. Geog. 2015, 39, 460–482

- Yang, X.; Hao, Y.; Cao, W.; Yu, X.; Hua, L.; Liu, X.; Yu, T.; Chen, C. How does spring phenology respond to climate change in ecologically fragile grassland? A case study from the Northeast Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12781.

Source: Plant phenology is an important bioindicator of climate change, Klimeteka

The author Roman Rachkov is part of the Klimeteka editorial team, he is an agronomist, a specialist in tropical and subtropical agriculture, and a long-standing expert in integrated and organic plant protection. He is Chair of the Bulgarian Association for Biological Plant Protection and has interests in the field of invasive insect species in Europe.

![MultipartFile resource [file_data]](/assets/img/articles/заглавна-фенология-1.jpg)